It is often said that the family is a microcosm of society at large. As Filipinos, we make a big deal about how our close familial bonds gave rise to our warm and caring culture, how we value spending time with our families, and how love is often defined within the context of building and nurturing a family. It is what drives our lives and influences the decisions we make: we live our lives in the service of others. This is the final taboo in Philippine society, the gilded belief in the sanctity of marriage, of family, that Mike De Leon’s controversial masterpiece “Kisapmata” shattered in the middle of the waning years of Martial Law. Tackling themes of patriarchy, domestic abuse, and the deeply chilling darkness that hides behind the seemingly perfect portrait of Filipino family life at the time. Given new life by Tanghalang Pilipino for its 38th season, the new theatrical adaptation penned and directed by Guelan Luarca, “Kisapmata” has proved once again that this has been undeniably a thrilling time for Philippine theater.

The film and the current adaptation are based on Nick Joaquin’s “The House on Zapote Street” from his collection of non-fiction articles “Reportage on Crime”. Kisapmata follows the story of the Carandangs: Dadong (Jonathan Tadioan), the authoritarian father, Dely (Lhorvie Nuevo-Tadioan), his long-suffering spouse, Mila (Toni Go-Yadao), his daughter, and Noel Manalansan (Marco Viaña), Mila’s husband. The story takes the audience on a forensic journey through the events that unfolded into a sensational and tragic end to all the lives of those who lived in the house on Zapote Street. In the end, all but one family member died in that house: but in cases such as these, the survivors fare no better from the slain, as they walk away with the unimaginable burden of telling the tale, bearing witness to the unimaginable horrors wrought by the ones they hold most dear.

The play endeavors to retain the unbearable atmosphere of the Philippines in the early 1980’s, while keeping the production fairly minimal. The set design by Joey Mendoza, while spartan in its form, carries with it a vintage sensibility that is oppressive in its openness. Its brutalist soul expressed in the way things are lit (D Cortezano) and how the characters interact with the space through movement (JM Cabling)—tiptoeing around parts of it much in the same way they walk on eggshells around the family patriarch. But above all these, in terms of establishing atmosphere, the sound design by Arvy Dimaculangan takes center stage. From the deceptively calming sound of wind blowing through tall grass, to the simple score that effortlessly imparts tension and suspense, the backmasked sound effects that instinctively imply a brisk, forward movement in time and space, and the deafening silence that exists in the negative soundscape that precipitates the implied terror in the unnatural stillness in between the characters of the play, it is a masterful exercise in auditory drama.

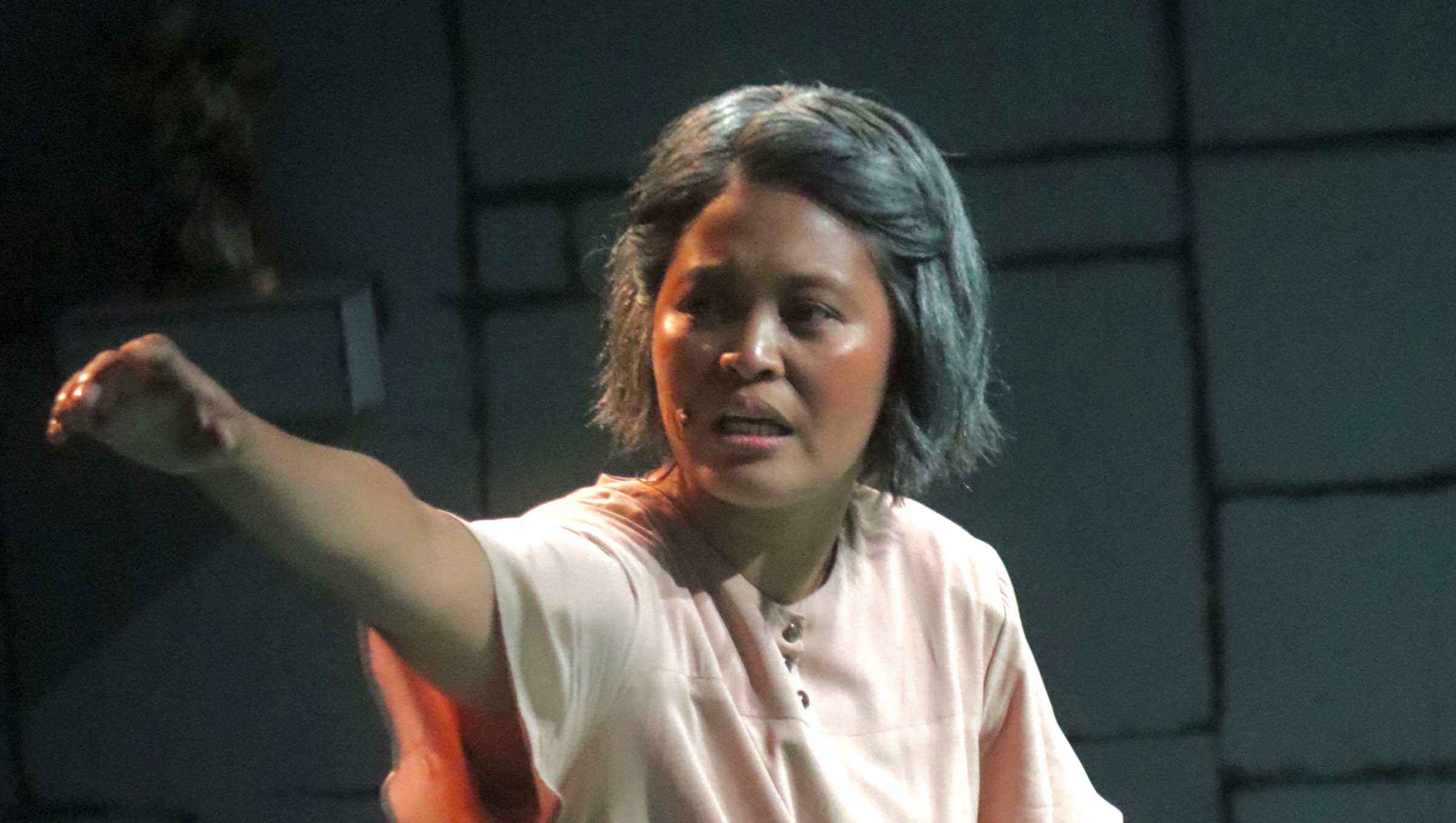

The original Mike De Leon movie was a comment on the oppressive Marcos regime that culminated in the imposition of Martial Law in the 70’s: with Dadong standing in for the cruel police state that not only abused and terrorized its citizens, but hurt and harmed them in very real, physical ways. Imelda Marcos’ “Love” initiative is writ large in how the cruelest, most barbaric wholesale curtailment of personal and civic freedoms is supposedly done “in the name of love”. The same is true in this adaptation, with the character of Dely (Nuevo-Tadioan) airily repeats the line “The Law of Love/Love is the Law”, her characterization of a woman driven beyond the point of survival and desperation, into what can only be described as living half a life. Her blank gaze, and almost incomprehensible supplication is equally horrifying and captivating at the same time. Playing opposite, Dadong (Tadioan) switches so effortlessly between benign, amiable, and quietly manic. Through his subtle machination and manipulation, ironically amplified by his soft, almost imperceptibly quiet voice, unsettles the audience from the first time he steps onstage, as he subverts what we have come to expect. Compared to the portrayal of Vic Silayan, Tadioan’s Dadong is more in line with any other paterfamiglia, his manner softer, which hides the danger more effectively. It does become clear, very early in the progress of the play, that the audience isn’t dealing with the usual happy family dynamic.

Perhaps owing to changing attitudes towards the same overbearing patriarchal structures that have often covered up the darker aspects of our society, the unimaginably horrific charge of incest, which lay in the heart of the story is more fleshed out in this adaptation than in the film. It is a compelling exploration of the complicated web of love, loyalty, and duty that as Filipinos, we instinctively know and often assume without any examination, and how these unspoken social rules are enforced by the people we trust the most. It is in the intersection of unconditional love and fidelity where you find the most terrible hazards. The play forces its audience to sit through, and witness this awkward terror. There is no looking away from this. And this abuse is made even more chilling by the fact that it is real, and that it is still happening to countless women and children across the Philippines.

Kisapmata is a beautiful reminder of theatre’s role in society. It is meant to depict real life through the lens of artifice: To shine a light on social realities that audiences need to pay attention to and educate themselves with in order to create real and lasting change. Consistent with the theme of Tanghalang Pilipino’s 38th Season, it is meant to ignite action against the prevailing culture of misogyny and is a call to dismantle and revolt against the oppressive systems fueled by the patriarchy. It is a twisted love letter to the death knell of a violent, inhumane aspect of being Filipino that couldn’t die fast enough.

The house on Zapote Street will eventually be consigned to the ravages of time, but its story will endure. The lessons enclosed within the lines of Joaquin’s writing, in between Mike De Leon’s celluloid frames, and onstage at the CCP’s Tanghalang Ignacio Gimenez, should never be overgrown and forgotten amidst the swaying of the tall grass. Despite your possible aversion to the sensitive topics that will be presented (or perhaps in spite of the same), It is unmissable theatre. In your discomfort: learn.

Click here for more stories like this. You may also follow and subscribe to our social media accounts: Facebook, YouTube, Instagram, TikTok, X, and Kumu.